In the second part of his series on the 1917 Australian general strike, Luke Boulby discusses the factors that led to the outbreak of this militant strike.

Quantity into Quality

The cost of living had been steadily rising over the course of the First World War. Before the general strike on 2nd August, average price increases were 33% above their pre-war levels. Real wages had also fallen by about 20% during this time. While the workers were told that certain sacrifices had to be made during wartime, the capitalists had made enormous profits from the war. The workers were not blind to this either. They had seen how profits had soared whilst they had to receive massive reductions in living standards. It would only take a spark to light this powder keg. As is often the case in such great events, the ‘Great Strike’ started from an accidental incident. The introduction of a card system by the Railway Commissioners as an attempt to speed up work was that spark.

The preceding period before the general strike had seen an upswing in strike activity. Far from cutting across the labour movement, the year the war started in 1914 saw a sharp rise in the amount of strikes and the workers involved in them. The Labor and trade union leaders had kept a check on the militancy of the workers, to a degree, through the use of compulsory arbitration courts to negotiate with employers for the workers’ demands.

In 1916, Billy Hughes, who was the Labor Prime Minister, had passed through a referendum to introduce conscription. The vote was lost narrowly by 2% against conscription and consequently the Labor party expelled Billy Hughes and his supporters for their support of conscription to the war. Billy Hughes, with his chauvinist fellow travellers, then formed the ‘National Labor Party’ before merging with the Liberals into the ‘National Party’. 1917 saw the election of Billy Hughes to the office of Prime Minister for a second time.

This government then went on the offensive which provoked the workers into action. As one of its first attacks, the government began to implement a card system in the Railway industry which would be used to measure how long it took for workers to complete certain tasks; the result would be to intensify the exploitation of the workers and fire those who were too ‘inefficient’. This system had been attempted in 1916, whilst a Labor government was in power, but was scrapped following negotiations between the government and union officials. It was re-introduced in 1917, and this time the government was fully prepared to fight it out till the end.

Following a mass meeting of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (ASE) who were affected by this card system, it was decided that they would refuse to work as long as the system was in place. The Secretary of the Labor Council of NSW, E. J. Kavanagh, announced a meeting between the Railway Unions and the Labor Council. The next day, representatives from both these bodies went to the Railway Commissioner and he told them that the card system would not be withdrawn under any circumstances. When delegates from the various Railway Unions heard the news, they passed a resolution stating that unless the card system was scrapped, they would stop work on 2nd August.

The resolution was carried by a number of unions representing workers from engineering, electrical, plumbing, metal, transport, timber, and other similar industries. However, no plans were ever set to whether all of these unions would stop work or whether it was just those affected by the card system, i.e. the railway workers. Although the government had made it known to them that they would not withdraw the card system, the trade union leaders still hoped that a compromise could be achieved. Kavanagh met with the Commissioner the day after and presented him with the ultimatum. The Commissioner dug his heels and stated that the card system would not be withdrawn. The Commissioner had thrown down the gauntlet by drawing up and announcing plans for the reduction of train services as an act of provocation.

The trade union leaders had pinned their hopes on the Government backing down and resolving this issue through the arbitration courts like it normally would. However, these were not normal times. Because they didn’t expect the government to fight back, they consequently didn’t make it clear to the workers in these unions what would happen on the 2nd August if the card system was not withdrawn. The initiative was left to the workers and they did so courageously. When the 2nd August came, there was a staggered process to workers joining the strike. Workers in Randwick and Eveleigh Railway Workshops came out on strike with small isolated groups from other workshops and depots joining them. However, only 5,780 workers came out on strike by the first day compared to the 42,000 workers in the whole rail and tram service. By the next day, other workers were brought into the strike. The engine drivers, cleaners, boilermakers and other workers came out on strike. Although they had hoped such a situation wouldn’t occur, by the scruff of their necks, the trade union leaders had been thrown into action by the rank and file.

The ‘Great Strike’ Begins

On 5th August, a meeting between the Locomotive Engine Drivers, Firemen and Cleaners’ association and the Amalgamated Rail and Tram Service Association decided to join the strike. All rail and tram services were declared to cease at midnight. However, the lack of co-ordination between unions in this trade meant that a number of workers still remained at work.

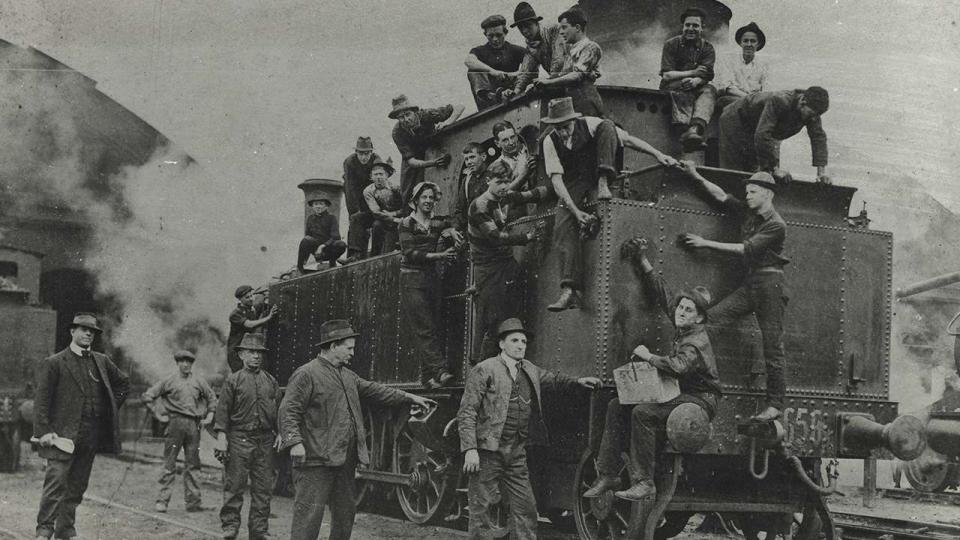

Despite this, the 660 trains that normally ran were reduced to 34. By the end of 7th August, the figure stood at 30,000 workers being on strike, involving some 18 unions. However, of the workers employed by the Railway Commissioners, 40% of workers were still in work. This was mainly down to the lack of unity and organisation between these unions. Miners, drivers, dockers, and metal workers would join the strike on 9th August; the figure now stood at 45,000.

Despite the government threatening the strikers that they would be subject to victimisation if they did not return to work, on 10th August, the last day of the ultimatum presented to the strikers, the workers held out. Three days later, the government announced that all rail and tram workers on strike would be dismissed and the unions would be forced to deregister. The government was talking the language of class war. The union leaders, on the other hand, were determined to confine the strike to a purely economic struggle. One could imagine the trade union leaders scratching their heads, thinking that if only the government could see how reasonable they were being, then maybe they’d change their mind.

Trade union officials of the NSW Trades and Labour Council had formed a strike committee called the ‘Defence Committee’ and attempted to negotiate with the government. The Defence Committee published a document detailing how inefficient and incompetent the running of the railways had been and demanded a Royal Commission to investigate these charges. They stated that the card system was the spark which set off the strike, because the workers did not trust the Railway Department due to gross corruption and mismanagement. However, the government had already set out that it would set up a Royal Commission after the card system had been implemented for three months. The government could sense the weakness of the union leaders and decided to push further. Instead of extending the strike to other sections of the working class and bringing them into the struggle, the Defence Committee had played into the hands of the government by further confining the aim of the strike.

Instead of narrowing the scope the strike, the trade union leaders should have fought the government back on the political front. They should have pointed out how the workers were being made to pay for this war whilst the capitalists were amassing enormous profits from the war. They should have pointed out that the government was using the war as a pretext to tear up the rights which had been bravely fought for over the preceding period. By exposing the role the government was playing with its open collaboration with the employers to smash the strike and ultimately the trade unions, the trade union leaders could have won the support of wider sections of the working class and could have had changed the tide of the fight.

The government stepped up their efforts to break the strike. By 14th August, the Railway Commissioner had implemented the mass dismissal plan and the government gave itself the power to seize all private motor vehicles for the duration of the strike. On top of this, this day was the day of the first arrest of a union official connected with the strike. Vice President of the Seaman’s Union, W. Daly was charged with conspiracy to instigate an unlawful strike whilst the seamen were considering joining the strike. On August 17, three more union leaders, E. J. Kavanagh, A.C. Willis, and C. Thompson (of the Amalgamated Railway and Tram Service Association), were arrested and also charged with conspiracy.

The Federal Government stepped in on the pretext of the strike breaking the War Precautions Act and set up the National Service Bureau to organise scab labour if the seamen joined the striking workers. The NSW Government also passed a number of bills further extending its powers. It was now under no obligation to maintain supplies to the public. It could also employ inexperienced labour in the coal mines and gave the miners until 23rd August to return to work before they would place ‘loyalists’ to take over their jobs. The Federal Government also took drastic action on 20th August by empowering the Navy to transport coal in the Commonwealth and to distribute supplies for industrial and other purposes.

Cracks began to show in the leadership of the Defence Committee which the government exploited to full effect. On the same day as the intervention of the Federal government, the Defence Committee proposed to the government that they would call off the strike if they would agree to modify the card system and guarantee that the striking workers would not be victimised on returning to work. The proposal was unsurprisingly rejected. The workers were not blind to the machinations of their supposed leaders. Consequently, the next day, the Defence Committee pivoted and denied that it was prepared to call off the strike and accept the card system, whilst appealing to the workers to remain steadfast.

The government reaffirmed its policy and announced it would no longer negotiate with the Defence Committee as it now declared it an illegal body. The Defence Committee, continuing to waver, stated:

“We are willing at any moment to resume work, and will agree to any other method of recording time, free from the degrading, features of the Taylor system … and we are now ready as we have been all along to meet the Chief Commissioner fairly in the matter, to resume work under neutral conditions and to pledge ourselves faithfully to abide by the decision of an independent tribunal on the system in dispute.”

Despite the compromising and appeasing attitude of their leaders, the workers morale remained high. Nearly every day, other layers of the working class would be drawn into the strike. By the end of the strike, 100,000 workers overall had been on strike across NSW, Victoria, and other states (but obviously at staggering periods) with the most ever out on strike at any one time was 68,000.

But by the end of August, the Government had been given ample time to organise a reactionary force to break the strike. When new workers came out on strike, within a couple of hours the workplace would be filled with loyalists.

Capitulation and betrayal

On 6th September, the Industrial Commission discussed with the Defence Committee for two days until the Defence Committee finally announced their unconditional surrender. Naturally, there was immense anger and hostility of the workers towards their ‘leaders’ for this betrayal.

Despite the capitulation of their leaders and the Defence Committee, however, some sections of the working class would still continue to strike. The miners would only return to work a month later on 3rd October. The seamen and dockers would strike even longer, but they would return over a month later since the official end, on 18th October. This was when the government finally decided to release the imprisoned union officials. Although the strike would eventually fizzle out, some isolated sections would stay out on strike as late as December. Even though the government had told the defence committee they wouldn’t victimise workers, when the workers returned to work, they were given a good lashing by the government and the employers.

The bosses went on the offensive following the defeat of the strike. Billy Hughes would also try another referendum on conscription but, although the strike had been a big defeat for the workers, not all their power had been expended and the second referendum was subsequently defeated by an even greater margin than before. The working class would regain its strength and another strike wave would occur in 1919. They would not forget what had taken place during this strike and consequently learnt some of lessons of this strike – even if their supposed leaders hadn’t.